Up until a few years ago, I used to make an annual “back to my roots” pilgramage to visit my parents who lived just outside the old mill/market town of Wigan, in Northern England. Halfway between Liverpool and Manchester on the Leeds-Liverpool canal waterway system, Wigan was an important player in the Second Industrial Revolution (in the 19th and early 20th Centuries).

Some readers may know about this region from reading George Orwell’s 1937 book, The Road to Wigan Pier, a sociological investigation of pre-war working-class living conditions in Northern England. (And, yes, Wigan really does have a pier that was designed for loading and off-loading shipped goods.)

Now a busy recreation waterway, the Leeds-Liverpool canal system once served dozens of mill towns and hundreds of cotton mills across Northern England. Those operations would receive raw cotton from the Southern United States, then deliver finished cotton goods to the rest of the world. As one of the dampest places on the planet and with access to abundant coal, this region was an ideal location for processing cotton.

One of the highlights of my trips home was to walk from my parents’ house via the path (formerly used by horses to pull barges) that runs by the canal, into the town of Wigan. Along the way, I would often stop in for a visit at one of my all-time favorite places: the historic Trencherfield Mill.

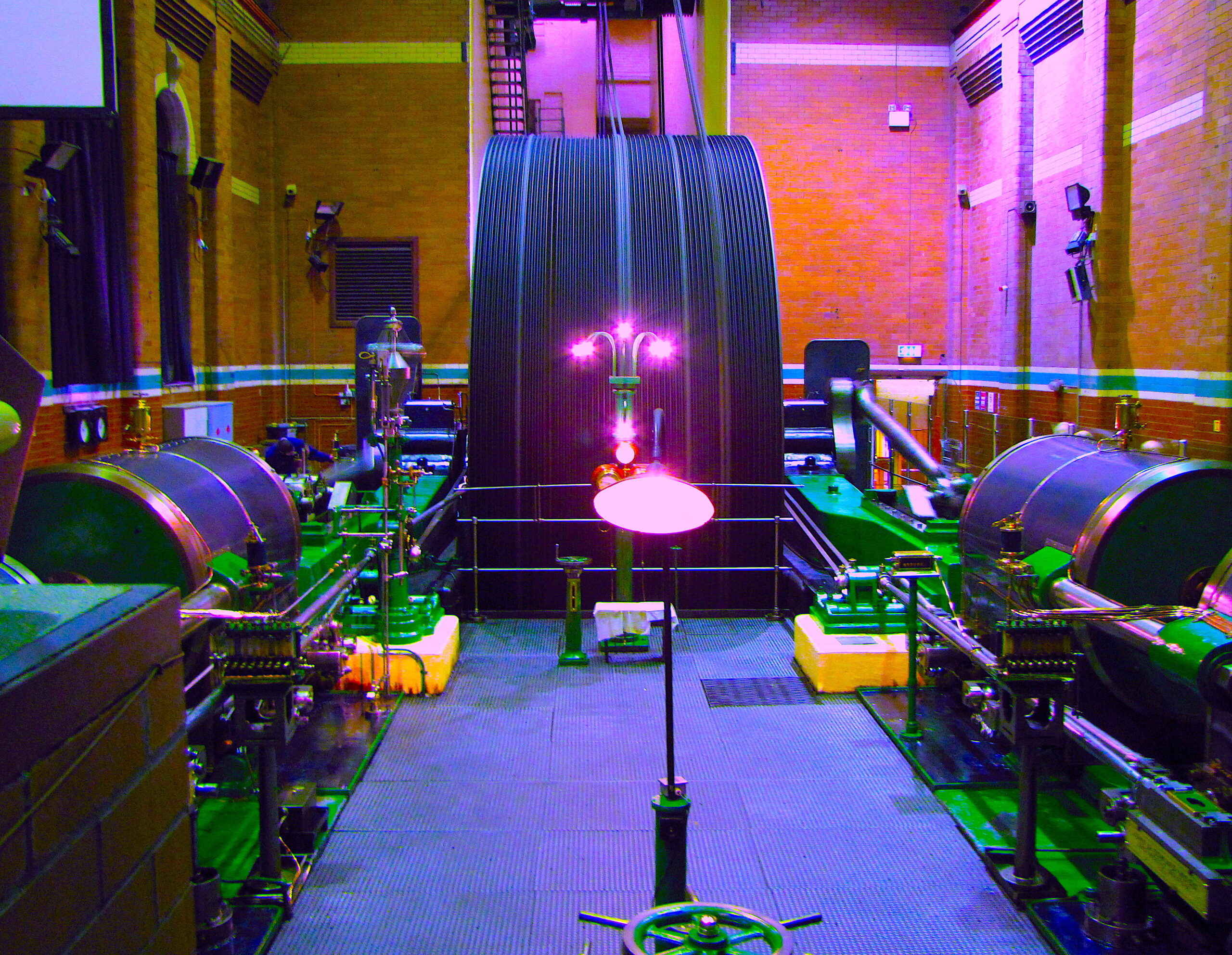

Built at the turn of the 19th Century, this once-busy cotton-carding and -spinning mill has been turned into an industrial museum. Although now temporarily closed due to COVID-19, the site houses the last and largest-ever built-in-situ, double-acting, triple-expansion, working steam engine in existence.

Commissioned in 1906 and fed by six boilers, that 2,100-hp tandem, horizontal, four-cylinder behemoth was fitted to a 26-ft.-diameter, 70-ton flywheel that connected the engine by way of a cotton-rope-driven-line-shaft system to more than 1,200 machines spread over five floors.

J.E. Woods steam engine at the historical Trencherfield Mill site,

Wigan, Greater Manchester, England.

Keeping this solitary steam engine running at a 100% capacity, 68 to 75 rpm, for 12 hours per day, translated into steady work for 450 mill employees. Downtime meant no pay and wasn’t an option. Effective maintenance was crucial.

On some visits to Trencherfield Mill, I had the opportunity to speak with Mike Prescho, the Senior Engineer in charge of the museum’s treasured steam engine for modern-day presentation purposes. I have always been curious about the mindset of those charged with running such a critical piece of machinery in its production heyday. As Prescho described it, they would “run it like a religion.” He would then elaborate on the individuals’ strict adherence to protocol, processes, and a calendar of PM (preventive-maintenance) events that never wavered in on-time completion.

Prescho also pointed to cleanliness, effective lubrication, and regular boiler washouts (thanks to dirty canal water) as major factors in the equipment’s incredible uptime and reliability record. Museum visitors are able to see actual examples of this approach for themselves.

Among other things, during a true-to-life demonstration of the Trencherfield Mill steam engine, I observed all critical main journal bearings being hydrostatically hand pumped with 220-weight lubricant prior to startup of the engine. Once the unit was running steady, the bearings were switched over to a cyclic, arm-driven, auto-luber that provided continuous lubrication. When the engine was shut down, everything was meticulously cleaned.

FINAL WORD

Amazing, isn’t it? Industrial-revolution-era engineers and millwrights had no backup systems. Instead, they simply adhered to process, procedure, cleanliness, and principles of lubrication for their assets’ reliability. Some things never change, nor should they. We have seen that reliability does not have to be complicated.TRR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ken Bannister has 40+ years of experience in the RAM industry. For the past 30, he’s been a Managing Partner and Principal Asset Management Consultant with Engtech industries Inc., where he has specialized in helping clients implement best-practice asset-management programs worldwide. A founding member and past director of the Plant Engineering and Maintenance Association of Canada, he is the author of several books, including three on lubrication, one on predictive maintenance, and one on energy reduction strategies, and is currently writing one on planning and scheduling. Contact him directly at 519-469-9173 or kbannister@theramreview.com.

Tags: reliability, availability, maintenance, RAM, asset management, Second Industrial Revolution, steam engines

.