Take it or leave it, the discussion of greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions has been relatively dominant in energy industry circles since the early 1990s. These days, industrial operations look to projects that will reduce energy (which directly impacts the bottom line) and also demonstrate a company’s social responsibility through emission reduction. Such efforts include many contracts in which the customer or client requires an environmental statement as part of the terms and conditions with any contractor or subcontractor.

What impact does the physical-asset-management community have on those boardroom-level concerns? As it turns out, there’s not just a correlation between maintenance, energy use, and emissions. There’s a direct and measurable link.

Since the early 1990s, those who have followed my writings know that I often tie energy and GHG emissions to corrective actions. This is a direct result of work that was performed related to the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (EPACT92) and attention it received from the asset-management community. As part of that initiative, significant work related to commercial facilities and energy-efficient home appliances was done. But it soon became clear to the program managers at the U.S. Department of Energy (USDOE, energy.gov) that maintenance practices were directly linked to energy management. Over time, USDOE’s promotion of repair-versus-replace programs, site energy surveys, and a variety of public tools that we’ve discussed in the The RAM Review, has had a direct (positive) impact on energy demand and emissions.

In 1994, another new concept basically turned the power-utility industry on its head. Following the successful deregulation of natural-gas utilities, the U.S. government made the decision and drafted laws at state and federal levels, to deregulate the electric-power industry. Whereas it used to have large, centralized power plants and “rolling reserves,” the industry had to do an about-face in to reduce power- generation operating costs. One advancement that came with deregulation was a broad shift in traditional power-generation types to technologies such as landfill-gas and natural-gas-peaking plants, which could respond quickly to replace expensive rolling reserves. Other research related to energy production increased in the late 1990s, including wind generation, solar power, fuel cells, and a variety of new concepts.

After the turn of the century, the application of alternate (now referred to as “green”) technologies was on the rise. While there have been concerns related to the variability of some new energy sources, the overall result has been a continued decrease in carbon emissions and a solid mix of energy technologies coupled with new energy storage methods to protect the robustness of the grid. This, in turn, has brought about a number of challenges, which continue to be addressed through the power industry and federal government.

From those involved in environmental-responsibility discussions and/or global government discussions, the push is toward electrification of the economy. This is not a new vision. It was championed by the likes of Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, George Westinghouse, and other innovators, starting as early as the 1800s. Those three named individuals, in particular, foresaw a time when everything would be electric-powered (with Tesla seeing earth-friendly generation through wind, solar, ether [yes, this was a thing], and hydroelectric). Tesla, by the way, was swayed toward coal (by J.P. Morgan), and developed one of the first ultra-efficient turbines for turning generators with steam.

Today, we see concepts from the late 1800s, including such things as wireless energy and high-voltage DC distribution systems, being re-addressed. Automobiles have slowly been making the transition back to original electric designs, and, now, hybrids, although with many of the same problems and range of concerns associated with earlier offerings. In fact, along with the evaluation of a new thing known as the “smart grid,” some of the investigation into a robust grid is making individual vehicles part of a power system in which utilities will charge and discharge them to meet power demand.

The real question is whether any of this has really had an impact. The next question is how the physical-asset-management community can impact the draw on electric power in our facilities.

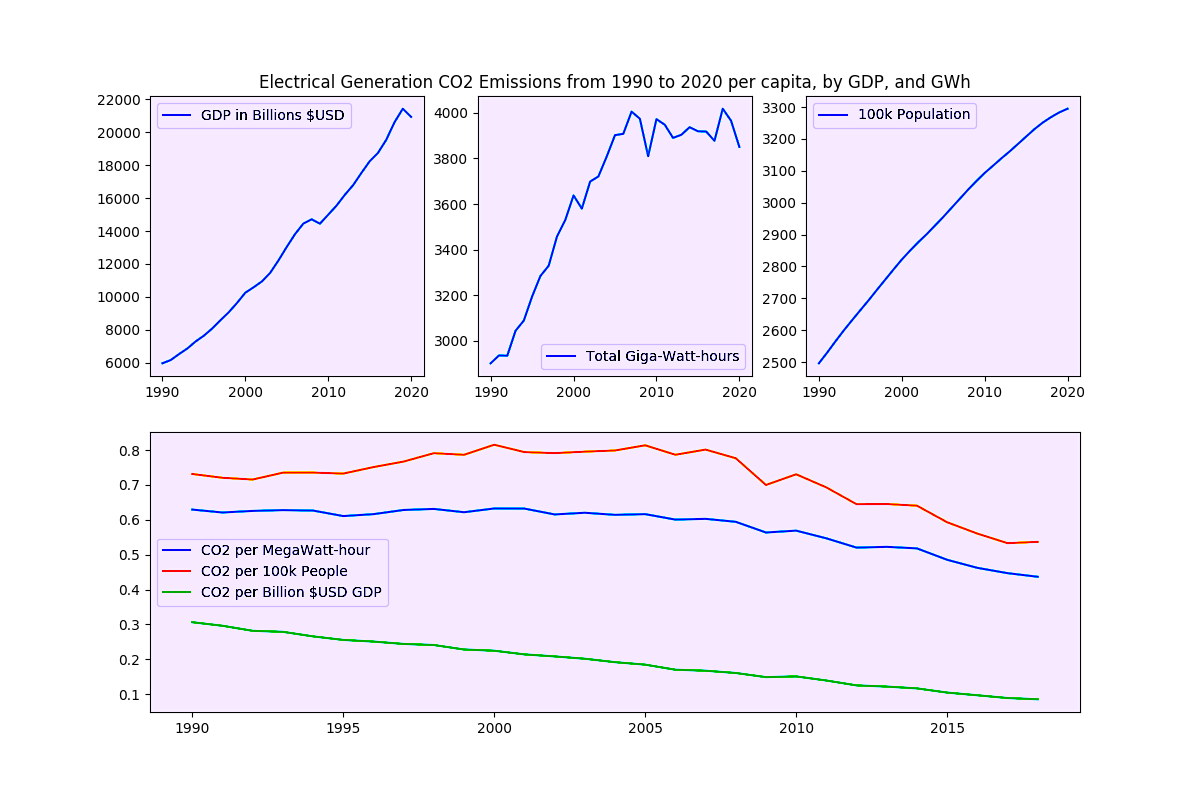

Fig. 1. GDP, Population, and Power Generation Relation to CO2 Reduction.

(Source: USA Energy Information Energy Administration https://eia.gov.)

With the U.S. economy and population growing, the demand on electric power is increasing. If we were to remain in the status quo, CO2 emissions from power production would continue to rise and our air would be challenging to breathe. However, as shown in Fig. 1, the trend in direct relation to each of these problems is down.

In the case of CO2 per Mega-Watt (MW) hour and U.S. GDP, this trend has been downwards for some time, with a steeper curve starting after 2005 for both emissions per capita and MW hours. Some of this reduction is directly attributed to the information in Fig. 2.

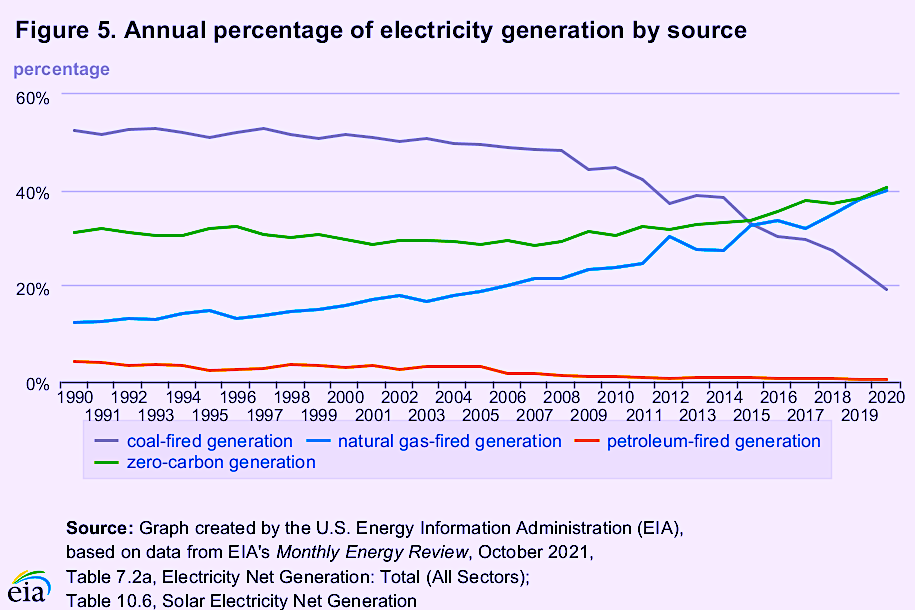

Fig. 2. Source https://eia.gov.

Even more interesting is the fact that total emissions have been decreasing in raw numbers since the early 1990s, mostly due to energy-saving efforts and changes to the mix of power-generation sources. In effect, the efforts of all involved have had an enormous impact on energy use. A substantial part of that is management of physical-equipment assets.

Over the course of 2022, I will be returning to this subject and identifying connection between physical-asset management, energy, and environmental and individual efforts. As we discuss reliability and maintenance opportunities, we also will be providing information on the relationship of those opportunities to energy, environmental, and profitability goals of today’s industrial enterprises.TRR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Howard Penrose, Ph.D., CMRP, is Founder and President of Motor Doc LLC, Lombard, IL and, among other things, a Past Chair of the Society for Maintenance and Reliability Professionals, Atlanta (smrp.org). Email him at howard@motordoc.com, or info@motordoc.com, and/or visit motordoc.com.

Tags: reliability, availability, maintenance, RAM, electrical power generation, energy efficiency, greenhouse gas emissions