A maintenance work order (MWO) is basically made up of three distinct sections. The first section, which was covered in The RAM Review article “Make Work Orders Work (Aug. 17, 2020), contains the general information required to raise a work order and make it an entity within the asset management system (AMS) software. The second (and arguably most important) MWO section covered in this week’s article is defined as the “Job Plan.”

The “Job Plan” section is the major instructional component of the MWO. and it is the primary responsibility of the planner to build a comprehensive work instruction set or package that includes identification of the trade group(s) and specific trade(s) who will perform the work detailed in the job plan/work instruction set. To complete the work package, the planner will also detail a list of required spare parts (if known), specialty tools, and permits to complete the job on site. Finally, to assist the scheduler in gaining access to the asset for maintenance purposes, pull together a weekly and daily work schedule for each trade group, tradesperson and schedule any required contractor assistance, the planner must assess and document the estimated time to complete the work.

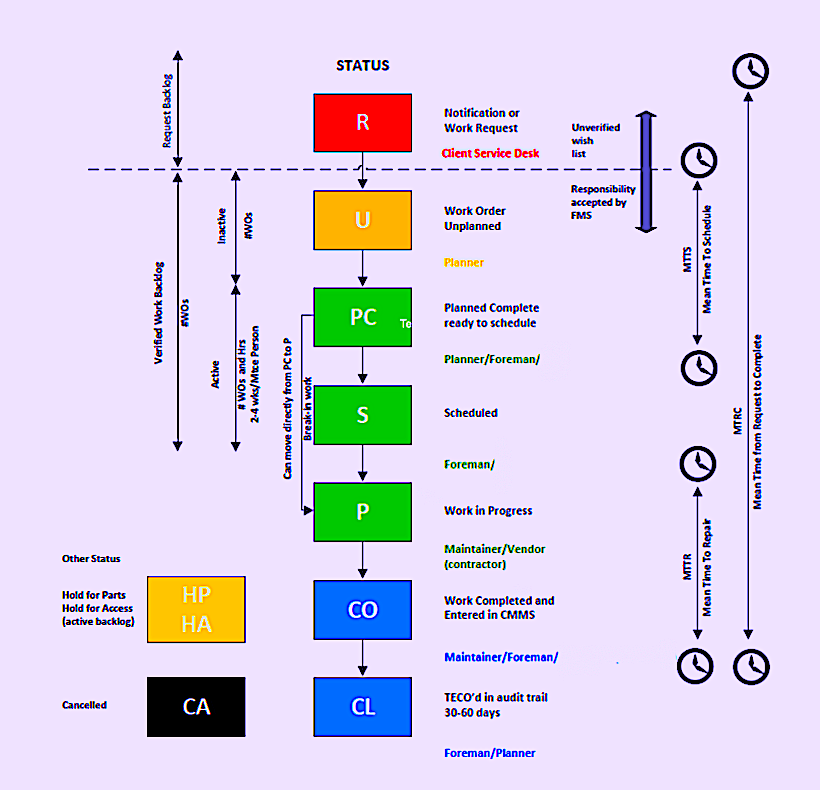

Once those tasks are complete, the work-order status (see figure below) can be updated from “U” (Unplanned) to “PC” (Planned Complete, Ready to Schedule) status. In doing so, the status change once again time stamps the work order as it moves from the inactive work order backlog on to the active work order (to be scheduled) backlog. These time stamps allow us to look at planner performance by monitoring the mean time to convert an unplanned WO to a planned WO, so as to determine if the planning department is understaffed.

A typical work-order-status workflow

(Copyright EngTech Industries. Inc.)

WORK ORDER BREAKDOWN: JOB PLAN SECTION

If a work order is going to be skeletal, the job plan or work instruction set is usually the area that is forsaken the most. In the absence of a full time planner position, or when a planning department is understaffed, a one-line work instruction replicated from the requestor is not unusual to see, and in too many cases a maintenance operation effectiveness review/audit discovers work orders that contain NO instructions, in which case the MWO number is used to only charge time (Usually for payroll and back charges) and purchases against. There are only two work order types, that require a one-line explanation: the Emergency WO and the Investigative WO (see The RAM Review article “Understanding, Classifying and Tracking Work,” June 5, 2020).

Emergency WOs: Because there may be no time to determine a job plan when an emergency event occurs, the Emergency WO is the only type that requires little or no descriptive details. Rather an Emergency WO is used to quickly muster trades to the event, and specifically to purchase any immediate required parts against. Once the emergency is over, the expectation is to capture and record all time taken, parts purchased, and a written narrative of work performed to include in the asset’s history files and use this information for any resulting investigations. Use of the Emergency WO type designation is to also instruct the scheduler to set up the work immediately.

Investigative WOs: If the planner is unable to ascertain enough information to understand the exact work requirements, and is unable to view the failure or maintenance problem virtually or first hand, an investigative WO is issued with a one line instruction that always begins with the action command “Investigate. . . ” Its primary purpose is to instruct the maintainer to assess the problem and act as a surrogate “eyes-on” planner to develop and document a relevant job plan and work instruction so parts can be ordered and work scheduled according to the failure consequence. If the problem is caused by a small issue such as calibration, adjustment, fastening, etc., and the fix can completed in situ by the maintainer in 15 minutes or less, without parts purchases, it makes sense for the maintainer to correct the problem immediately and update/change the work-order type to the appropriate designation (calibration, repair, etc.) on completion. All other work-order types will require a pre-planned work instruction set.

In pre-planned work, the planner’s responsibility is to facilitate the work process and ensure, as much as possible, the tradesperson performing work on location has all the pieces required to complete the work within the estimated time frame. The following informational fields are to be found in the Job plan section of the work order that act together to build a complete informational maintenance work package.

SAFETY REQUIREMENTS. . .

Due diligence dictates that we all adopt a safety-first approach toward work: The work order can’t make the maintainer work safe, but it can remind the him or her—every time—of the minimum expected safety equipment to be used and protocols to be followed throughout the work process, these will change depending on the work to be performed, the location of work, and the trade group performing the work.

Typical safety requirements will list the standard safety equipment. e.g., gloves, eyewear safety boots, etc., and can also include specialized equipment such as gas analyzers used when working around chemicals, gases or in confined spaces such as pits and vessels.

When working with energized equipment, the work order will serve to remind the maintainer about the need to follow any required safety standards such as lock out/tag out requirements. Any actions required by the maintainer to follow the standard can also be included in the actual job plan section narrative.

PARTS REQUIREMENTS. . .

The parts section of the work order allows the planner to list all known parts required to complete the job. In a planned, complete work order, the planner will ensure that all listed parts are in stock, pre-assigned to the WO number, and awaiting pick up by the maintainer. In advanced planning environments, parts are picked in advance by the MRO stores group, kitted together under the WO number, and readied for pick up by the maintenance group, in a defined staging area near the maintenance department, or pre-delivered to the job site, in preparation for and prior to the maintainer’s arrival at the site.

PERMIT REQUIREMENTS. . .

In most companies, health and safety standards dictate that permits must be issued for certain types of work performed, so as to ensure certain protocols are followed. These can include Hot Work permits, if welding or hot metal cutting is to be performed, or a Confined Space permit, if work is to be performed in a designated confined space area. Such permits also alert the plant management staff of the type of work being performed in their area ahead of time.

TOOL REQUIREMENTS. . .

Tools listed in this area typically reference occasionally-used common tools, expensive diagnostic tools, or special tools not expected to be carried in a maintainer’s toolbox. These are shared tools that are usually managed in a tool program by the inventory- management group, and require a WO number to pre-allocate the item for pickup or staging, as with spare parts.

REFERENCE DOCUMENTATION. . .

Part of the Maintenance Work Request (see The Ram Review article, “Maintenance Work Orders: The Request,” April 10, 2020) is to gather documentation and pertinent information relevant to the failure from the requestor. This will include any photographs taken of the at the time of the event (or subsequent to the event). In addition, any sensory information provided by the requestor at the time of the event discovery can be documented here, including anything that’s heard, such as unusual noise, (any audio file taken on a cell phone can be referenced here), or unusual smells, feelings (vibrations, heat), taste, and whatever else a maintainer’s intuition tells him or her.

Also included in this documentation area will be references to drawings, redlines, as-builts, especially where problems are suspected inside a machine or behind a wall. References can be actual drawings, photocopied drawing sections physically bundled as part of the work package, or drawings referenced electronically to be accessed by the maintainers laptop, tablet or cell phone on site.

TIME ESTIMATE. . .

A job-plan time estimate is usually given in hours and portion of hours. Most planners like to round off time to quarter or half hour increments for easier scheduling. The only exception to this is when the planning group uses Time Management Units (TMUs) to express time; these are usually in increment of 10 TMU per hour, or 6 minutes per TMU.

How job-plan estimates are calculated vary from company to company. The recommended method is for the planner to only allocate time for the work to be performed on the work order. Additional time for travel (which can vary throughout the day due, say, to traffic when work is not in the same location, or when a maintenance department is dealing with multiple sites); picking up parts and tools from their staging areas; time to log in with the department foreman, etc., can then be added by the scheduler. When the work order is closed, it is the difference between the estimated time allocated to perform work and the actual time taken to perform the work that is used to calculate a planner’s work estimation performance using variance reporting.

WORK INSTRUCTION. . .

This section contains the actual work instructions to be performed by the trade, or trades, if the job has a multi-trade requirement. All work instructions must be objectively written if the work is to be performed as envisioned by the planner.

There are two distinct methods of preparing work instruction. The first is for Preventive and Predictive work that’s pre-planned and designed to repeat multiple times throughout the year using the same job plan or instruction set. The second is for unique demand-type work that is a single occurrence and, thus, must be planned on an individual basis. The techniques and tools used for both of these types of work instruction will be addressed in another article.

COMING UP

The third MWO section is reserved for post-work data-collection and comments. Among other things, this includes checklists, which will be covered in next week’s installment of this “Make Work Orders Work” series.TRR

Editor’s Note: Click The Following Links To Read The Articles Referenced Above:

“Make Work Orders Work” (August, 15, 2020)

“Maintenance Work Orders: The Request” (April 10, 2020)

“Understanding, Classifying, and Tracking Work” (June 5, 2020)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ken Bannister has 40+ years of experience in the RAM industry. For the past 30, he’s been a Managing Partner and Principal Asset Management Consultant with Engtech industries Inc., where he has specialized in helping clients implement best-practice asset-management programs worldwide. A founding member and past director of the Plant Engineering and Maintenance Association of Canada, he is the author of several books, including three on lubrication, one on predictive maintenance, and one on energy reduction strategies, and is currently writing one on planning and scheduling. Contact him directly at 519-469-9173 or kbannister@theramreview.com.

Tags: reliability, maintenance, availability, RAM, work management, work order, job plan, work instruction, data collection, maintenance workflow, asset management