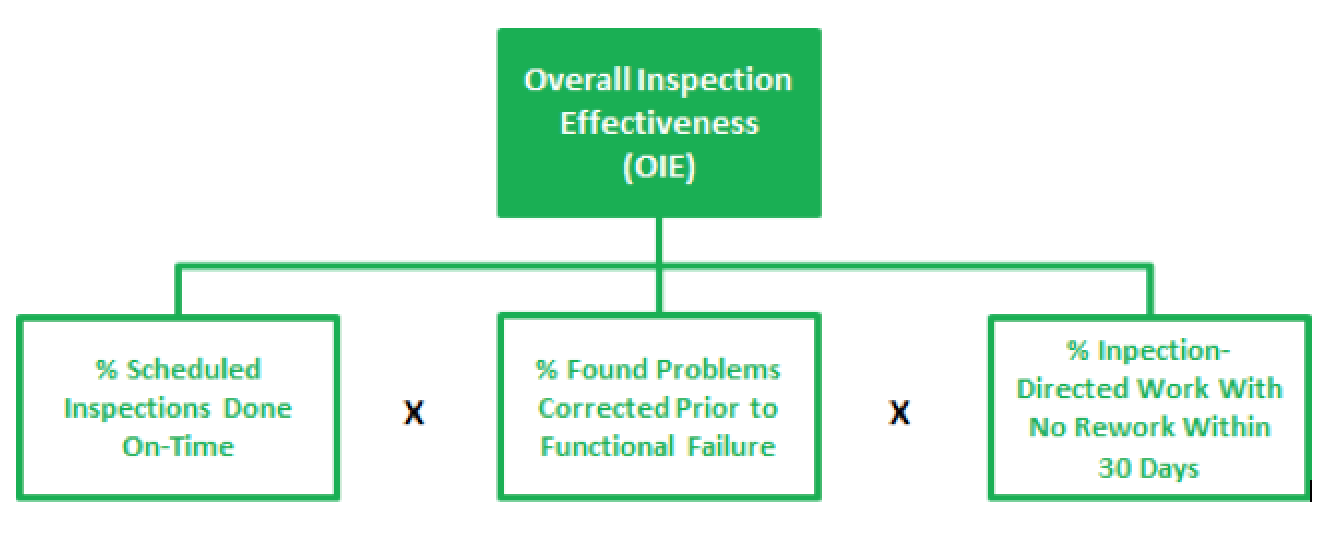

Inspections are essential to any physical-asset-reliability-management initiative. Thus, the importance of monitoring Overall Inspection Effectiveness (OIE) within your operations can’t be overstated. As depicted in the following chart, OIE is the leading metric for evaluating the critical-inspect-to-work process.

Sadly, few inspection programs are as effective as they could be (and should be). That’s due to what I call the “inspection trap,” which compromises the inspect-to-work process.

Here are some common ways the inspect-to-work process topples over:

-

- The inspection is scheduled, but not completed.

- The inspection is completed, but fails to discover or properly diagnose detectable problems.

- The inspection is completed and the problem is found, but the problems aren’t effectively reported in the form of a work request.

- The work request is submitted, but the job is not planned and scheduled in time to address the problem.

- The scheduled work was not executed or completed correctly.

Based on that list, it’s easy to see how the inspect-to-work process touches many other processes, including, specifically, the inspection process, the work-request process, the maintenance-planning-and-scheduling process, the maintenance-supervision process, and the work-execution process.

While I will address other elements of the inspect-to-work process in future articles, for now, let’s focus on managing the inspection process correctly.

INSPECT-TO-WORK-PROCESS COMPONENTS

1. Select proper inspections for machines, components, or classes of machines and components.

2. Determine appropriate inspection interval.

3. Organize inspections in to routes or work packets based upon:

-

- required operating state

- similarity of work requirements

- tools required

- geography of machines to be inspected

- inspection intervals

- work-management and manpower limitations.

4. Provide JSEA (Job Safety Environmental Analysis) instructions for completing the inspections or inspection routes.

5. Define the objective(s) for each inspection.

6. Specify the inspection point or location, utilizing photographs or drawing as required.

7. Specify acceptable and unacceptable conditions, to include fit, tolerance and quality details where appropriate. Pictures that contrast acceptable and unacceptable conditions are invaluable.

8. Specify tools and/or materials required to execute the inspection.

9. Provide required instructions for executing the inspection.

10. Describe what constitutes an acceptable or unacceptable condition. This may be visual/sensory, gauge-enabled or sensor-enabled.

11. Inspection execution:

-

- Was the inspection completed? Yes or No. If No, why:

a. Wrong operating state.

b. Couldn’t safely execute the task.

c. Got called away to other work.

d. Insufficient time.

- Was the inspection completed? Yes or No. If No, why:

-

- Was the observed condition compliant? Yes or No. If No, describe:

a. Define failure from a standard taxonomy.

b. Fixed as found.

c. Work request required (ideally selected from a list of standard jobs).

- Was the observed condition compliant? Yes or No. If No, describe:

IMPLEMENTATION TIPS

Inspections can be effectively accomplished using simple technology, such as a clipboard sheet and pen, or more sophisticated software-supported programs. The challenge with the clipboard-sheet-and-pen approach is that the inspection results sometimes don’t get reported. That scenario, in turn, compromises the next steps in the inspect-to-work process. Moreover, additional labor is required for data input.

The higher-tech options often carry a big price tag and may or may not enable execution the way you want it. Use this list as talking points to discuss what you want to achieve with your inspection process and how you wish to execute. This will help you in arriving at the best process for your organization.

Remember: Inspections are a foundational element in physical-asset management, and it’s often the launching point for effective maintenance work management. Be sure you measure twice and cut once in creating your inspection process.TRR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Drew Troyer has 30 years of experience in the RAM arena. Currently a Principal with T.A. Cook Consultants, he was a Co-founder and former CEO of Noria Corporation. A trusted advisor to a global blue chip client base, this industry veteran has authored or co-authored more than 250 books, chapters, course books, articles, and technical papers, and is popular keynote and technical speaker at conferences around the world. Among other things, he also serves on ASTM E60.13, the subcommittee for Sustainable Manufacturing. Drew is a Certified Reliability Engineer (CRE), Certified Maintenance & Reliability Professional (CMRP), holds B.S. and M.B.A. degrees, and is Master’s degree candidate in Environmental Sustainability at Harvard University. Email dtroyer@theramreview.com.