As a consultant, I support my clients with a variety of initiatives to improve the performance, reliability, safety, and environmental sustainability of their plant equipment and manufacturing processes. Sometimes these initiatives are small, given the fact we’re tweaking existing processes. In other cases, though, the initiatives are transformational in nature. And, when an initiative is transformational, it can be disruptive to the organization. That’s when we need to mount a serious change-management effort.

Most organizations suffer from some degree of psychological inertia. Individuals and groups of people tend to anchor to behaviors with which they’re familiar. In physics, a body at rest tends to remain at rest, or a body in motion tends to remain in motion unless it’s acted on by some external force. People and organizations tend to do the same thing, hence the term psychological inertia, which basically means resistance to change.

There’s a whole host of reasons for resistance to change. For example, people may be suspicious about the motivation for a change. Or team members may not be confident that they’ll be successful in a proposed new system or process. In addition, they may be personally or professionally anchored to the old way of doing things.

Organizational-change management must be executed with purpose and care. One question I routinely hear is, “Should the change be top-down or bottom-up?” In reality, most effective transformational change is middle-out. Let’s explore this in more detail.

TOP-DOWN OR BOTTOM-UP CHANGE MANAGEMENT

There’s a natural tendency to assume that to be effective, change must be managed from the top down. The assumption is that senior management have the authority to allocate resources and get things done. In a command-and-control organization, such as the military, this holds true. Some, however, will argue that a bottom-up approach is the way to achieve transformational change. The logic here is that the front-line workers are closest to the problem and, thus, have the clearest line of sight on solutions that will work.

These top-down and bottom-up approaches have some problems, though. Sometimes, when a transformational-change initiative is top-down oriented, folks on the front line don’t have confidence in its probability of success (and sometimes they’re right). I’ve seen top-down initiatives that simply don’t make sense, when viewed from the plant floor. Additionally, top-down initiatives are often viewed as “programs of the day,” and front-line people will just wait them out, i.e., until they lose momentum.

Bottom-up initiatives, on the other hand, actually work quite well for continuous improvement. For example, Toyota’s Kaizen program relies on incremental improvement based upon suggestions from front-line team members. Unfortunately, front-line workers often lack the resources, influence, and discretionary time to drive transformational change.

MIDDLE-OUT CHANGE MANAGEMENT

Humans are more change-averse when they’re pursuing gains and less change-averse when they’re protecting against losses or responding to a crisis. (That’s a well-proven psychological construct.) As a result, in the absence of a true crisis, clever CEOs will often create the perception of a crisis. The reason is those CEOs realize that most significant transformational- change initiatives are driven by their middle managers.

Middle managers are usually highly experienced and well educated. Moreover, they’re usually close enough to the process to create transformational initiatives that will actually work. And, just as important, they usually have enough credibility with front line team members to get the initiative implemented. So, when CEOs invent crises, they’re attempting to unleash the creative juices of their smart middle managers.

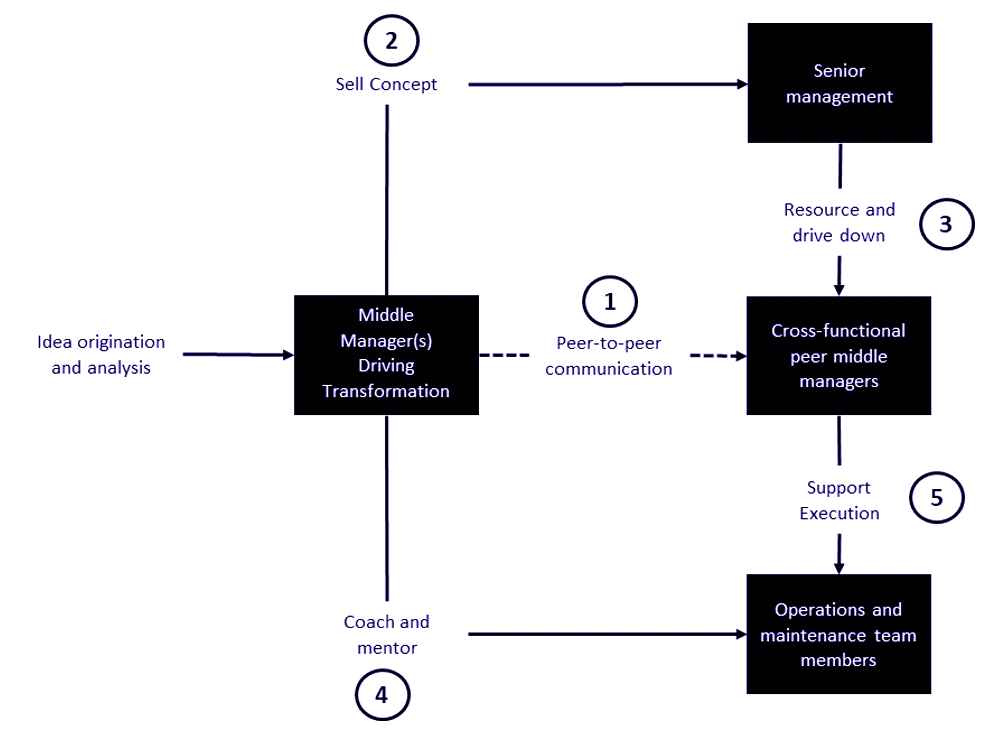

To successfully drive a transformational-change initiative utilizing the middle-out approach, we must, of course, have a good idea that it’s adequately fleshed out in terms of the technical and organizational aspects of implementation. We also must exercise due diligence to ensure that the proposed initiative provides an appropriate return on investment (ROI). If, after the due diligence, the initiative looks good, then we must go to work on the organizational aspects of change management. For simplicity’s sake, I’ve summarized this process and the very important, the sequence in which to proceed below (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Summary of a typical process for implementing/managing transformational change.

A common mistake in driving transformational change is for a middle manager to take his or her proposal straight up to top management. The problem is, top management typically won’t approve a transformational-change initiative project without cross-functional support for it, consensus on how to execute it, and a high likelihood of its success. So, the first critical step in middle-out change management is for the middle manager(s) driving such initiatives to reach out to their peers.

Let’s say you’re an engineering manager who is driving a change: You’ll want input and endorsement from the maintenance managers, operations manager, supply-chain manager, safety manager, environmental manager, and other appropriate members of management. Once you’ve reached a consensus of opinion and achieved a coalition of support at a peer-to-peer level, then you’re ready to move to step two, which is to present to senior management.

Senior managers like to hear proposals that are technically, organizationally, and economically justified, and which also reflect a consensus of opinion. Such projects typically enjoy a high approval rate. At this point, you’re ready to move to step three, which is to assist senior management in organizing resources, e.g., money, people, etc., and to support them as they message the initiative to the organization. This represents your “hunting license” to proceed with the initiative.

Steps four and five are covered together. With the support of your peer middle managers who’ve already bought into the transformational initiative, you coach, mentor, and cajole team members to help them understand the new way of doing things and, in the process, overcome their psychological inertia. That’s a topic we’ll address in more detail in next week’s article for The RAM Review.

BOTTOM LINE

Transformational-change initiatives are difficult. Very difficult, that is. If you’re a middle manager you’re in the best position to create, justify, and drive these types of initiatives. Remember, though, to be successful, you must work proactively to first gain input and support from a cross-functional group of peer stakeholders; then engage senior management for authority and resources; and, finally, coach, mentor, and nurture front-line team members in the execution of an initiative.TRR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Drew Troyer has over 30 years of experience in the RAM arena. Currently a Principal with T.A. Cook Consultants, he was a Co-founder and former CEO of Noria Corporation. A trusted advisor to a global blue chip client base, this industry veteran has authored or co-authored more than 250 books, chapters, course books, articles, and technical papers and is popular keynote and technical speaker at conferences around the world. Drew is a Certified Reliability Engineer (CRE), Certified Maintenance & Reliability Professional (CMRP), holds B.S. and M.B.A. degrees, and is Master’s degree candidate in Environmental Sustainability at Harvard University. Contact him directly at 512-800-6031 or dtroyer@theramreview.com.

Tags: reliability, availability, maintenance, RAM, change management, organizational change, workforce issues