When was the last time you performed an interior physical inspection of your oil-system reservoirs? Is performing a reservoir cleanliness check (interior and exterior) part of a regular preventive maintenance (PM) checklist for all hydraulic, recirculating-lubrication-system, and gearbox reservoirs at your site? If you answered “no” or “rarely,” those reservoirs may already be contaminated with the dreaded sludge.

Sludge is a manufactured byproduct that’s created through:

♦ Use of Incorrect oil (base oil, viscosity or additive package) for

the application and/or working environment.

♦ Cross-contamination with incompatible lubricants.

♦ Use of virgin oil that has been stored incorrectly or for too long

(see the Feb. 13, 2021 article, “Do Lubricants Have a Shelf Life?”).

♦ Over-extended lubricant and filter change cycles.

♦ Dirty oil causing excessive bearing wear material buildup.

♦ Introduction of dirt or debris into the reservoir.

♦ Introduction of water or moisture into the reservoir.

♦ Introduction of fuel or chemicals into the reservoir.

♦ Introduction of production materials into the reservoir.

♦ Subjecting reservoirs to large temperature-swing cycles that

create moisture condensation.

It’s important to note that any one or a combination of the above situations will speed depletion of the lubricant’s protective additive package through decomposition, separation, and absorption. Additives become insoluble and drop out; neutralize and turn into salt and water; morph into corrosive acids; and thermally degrade and oxidize. Once additives are depleted and oxygen, water, dirt, and and/or heat are present, the oil deterioration accelerates, leading to formation of varnish and tar on working components.

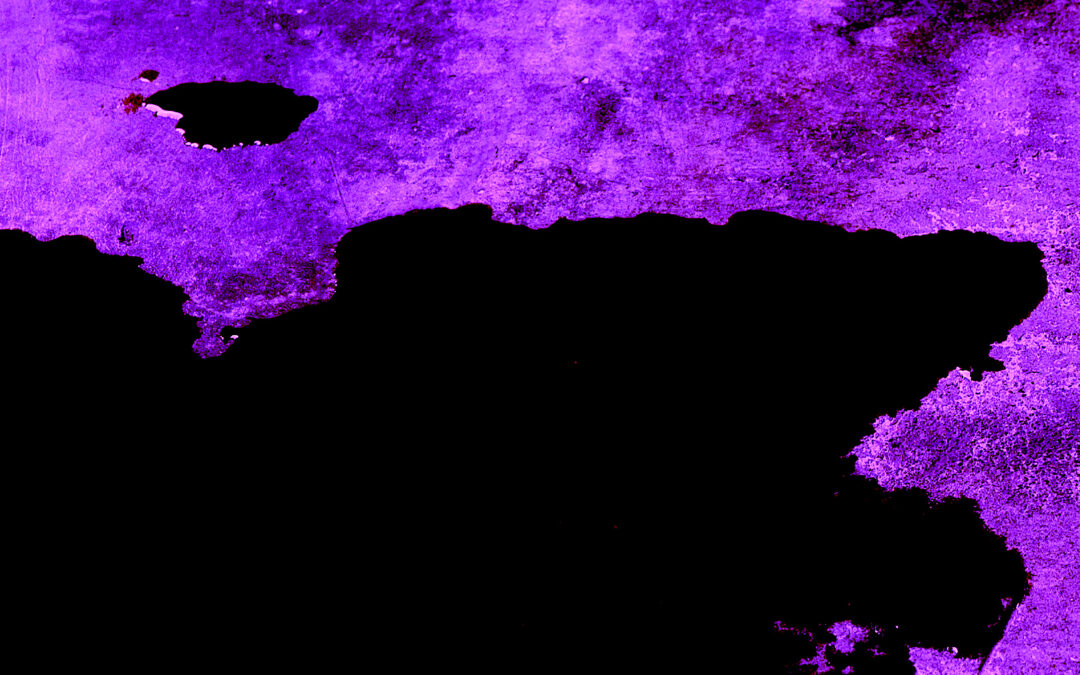

During the deterioration process, the oil thickens considerably, making it more viscous and difficult to pump through the system. At that point, the lubricant has become a black, gooey sludge that sticks to the reservoir walls and floor, leaving a liquid with little or no lubricating properties.

Click Here To Read The Author’s Referenced Feb. 13, 2021, Article

“Do Lubricants Have A Shelf Life?

PREVENTIVE MEASURES

It’s easy to inspect for the tell-tale signs of sludge, which should be listed on every lube-system PM checklist and oil-change work plan at a site. Sludge manifests as:

♦ Stained or discolored oil-sight-gauge windows or tubes that make

it difficult to assess the fluid level.

♦ An oil-level gauge that shows no lubricant in the reservoir after

filling (due to sludge blocking the sight tube).

♦ Slow lubricant release from the reservoir drain plug, even when

the fill cap and/or breather is removed.

♦ Oil-operating temperature that’s hotter than normal.

♦ Change in oil pressure.

♦ Physical inspection inside the reservoir (using a flashlight or

a visual-inspection camera system) that shows black buildup

on the tank’s walls and bottom.

♦ A black, gel-like substance that coats a finger placed in the

reservoir’s open drain port.

Keep in mind that it’s also easy to prevent sludge. If suspected or detected, though, this harmful goo must be removed at once and the oil reservoir cleaned as quickly as possible to prevent damage to the machine host. Cleanup involves the following steps:

1. Mechanically remove as much sludge as possible. Large reservoirs will usually have a clean-out plate that can be

removed to access the tank.

2. Remaining sludge can then be chemically removed. Use a recommended solvent-based flushing fluid, purchased

purchased from your lubricant supplier, for the specific lubricant type in the reservoir.

3. Ensure the correct lubricant is being used for the application’s ambient temperatures.

4. If not already in place, attach a label to the reservoir (or update the existing label) to clearly indicate the correct

lubricant manufacturer, product name, and viscosity to be used. Be sure to indicate/update the same information on

the PM work order.

5. Use contaminant-exclusion breathers (<5 microns, preferably 1 micron) for larger reservoirs, or bladder-type

expansion breathers for smaller gearbox reservoirs.

6. If the reservoir exterior is regularly cleaned with water, ensure that the fill cap and breathers (if applicable) are

waterproof and in place at all times. Or, alternately, position a water-deflection shield over over the reservoir.

7. When changing lubricants, make sure caps and breathers are always reinstalled, and that each lubricant is

transferred using dedicated clean equipment.

8. Always fill reservoirs to the correct level. Don’t overfill. Overfilling creates turbulence and air bubbles (oxygen)

that will deplete a lubricant’s anti-foam and anti-oxidant additives prematurely.

9. Use regular oil analysis to determine when to change lubricants or filter oil based on condition.

THE FINAL WORD

Sludge is an undesirable resident in any reservoir. A “tell-tale” sign of a neglected lubrication system, it indicates the current lubrication-PM approach is ineffective and damaging to the host machine’s health and life cycle.

In short, finding sludge in your site’s lube-system reservoir(s) should be treated as a wakeup call to improve your lubrication-management strategies and tactics.TRR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ken Bannister has 40+ years of experience in the RAM industry. For the past 30, he’s been a Managing Partner and Principal Asset Management Consultant with Engtech industries Inc., where he has specialized in helping clients implement best-practice asset-management programs worldwide. A founding member and past director of the Plant Engineering and Maintenance Association of Canada, he is the author of several books, including three on lubrication, one on predictive maintenance, and one on energy reduction strategies, and is currently writing one on planning and scheduling. Contact him directly at 519-469-9173 or [email protected].

Tags: reliability, availability, maintenance, RAM, lubrication, lubricants, additive packages, filtration, oil, grease, oil-system reservoirs, breathers, oil analysis, lubricant handling, lubricant-transfer